DIGITALISATION AND MODERNIZATION

The evolution of information and digital technology substantially impacts the capabilities of financial services firms and the Financial Services Industry (FSI) as a whole. Digital transformation necessitates the quick change of existing competencies and the development of new competencies expressly relevant to applying the digitalisation (Mavlutova & Volkova, 2019).

Customers are attracted to companies that can quickly market new and relevant products. Increased brand recognition and perceived value further benefit the product innovation (Agolla, Makara, & Monametsi, 2018). Customers’ expectations regarding accessibility, comfort, simplicity of use, and customisation have changed due to technological advancements, digitisation, and future legislation (Wójcik & Ioannou, 2020).

Financial institutions are adapting to the ever-changing customer needs and facing new competitors in the form of fintech companies. To stay ahead in the game, these institutions are adopting Agile/DevOps methodologies and utilizing cloud infrastructure to streamline their software release process. This approach helps them to release more secure, stable, and faster products that meet the evolving demands of their customers(Jelassi & Martínez-López, 2020).

RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH MODERNIZATION

Although the modern Agile/ DevOps way of working supports faster time to market, it also introduces new risks. Use of immature automated deployment tools, lack of knowledgeable resources, inconsistent security policies, and lack of standards and guidelines (Akbar, Smolander, Mahmood, & Alsana, 2022) are some of the critical risks which result in low-quality products.

Due to the nature of cloud there is also increase risks of data privacy, data breach, misconfiguration, credentials compromise, account hijacking etc. (CSA Working Group , 2020).

Dutch Central Bank (DNB) STANDARD OF GOOD PRACTICE

In the Netherlands, all the institutions under the central bank (De Nederlandsche Bank DNB) supervision are obliged to perform a periodic self-assessment which measures the institution’s operational maturity levels.

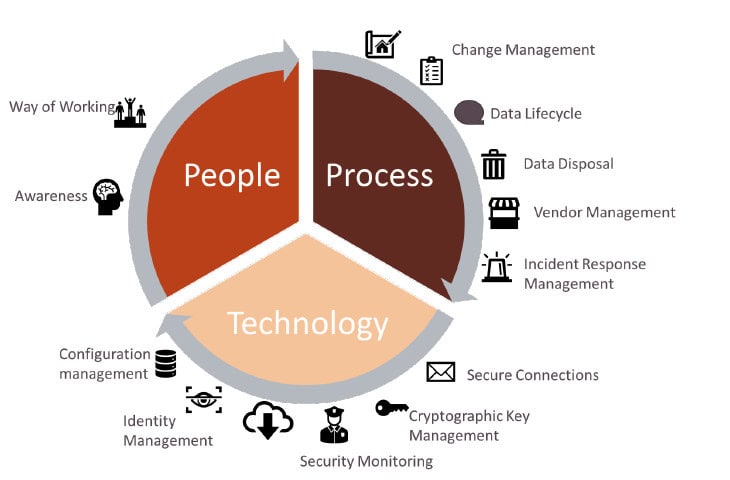

In the case of the Netherlands, the Dutch National Bank states (Dutch National Bank, 2019): “This Good Practices document provides the institutions under our supervision with practical guidance on the implementation of control measures to ensure the integrity, continuous availability and security of electronic data processing.” The document contains 22 themes and 58 control measures covering the topics of People, Processes, Technology, Facilities, Outsourcing, Testing, Risk Management Cycle, Governance and Organisation.

The institution must assess the control measures’ design, implementation, and operating effectiveness as part of this self-assessment. DNB expects the institutions under its supervision to have at least a maturity level of 3 out of 5 on COBIT 4.1, ranging from 0 (non-existent) to 5 (continuous improvement) for fifty-five control measures and a maturity level score of 4 for the three control measures in the Risk Management Cycle.

WHY EXISTING MAPPING DOESN’T WORK

Information security is essential, but the Agile/DevOps/Cloud teams need help understanding the principle-based DNB’s requirements or proving their security compliance. E.g. With the usage of pipeline, many traditional risks such as unauthorised changes to the environment, changes in configuration settings can be eliminated by addressing it specifically.

From our survey amongst practitioners in security in a regulated financial environment 93.9% had knowledge of a framework. To the question “To what extent does this good practice support the use of Agile/DevOps?“ respondents could score on a 1-5 scale, 5 being the highest support. Almost 46% gave a score of 1 or 2 which we can consider a negative response, 27% scored neutral and 27% gave a positive score.

The requirements from the regulatory bodies are translated based on existing knowledge of environment, process etc. The switch to cloud and modern way of working is still ongoing. So, there is a clash between the translation (which is based on the traditional environment) and the new modern way of working. Furthermore, each company makes its own translation of these principal-based guidelines. In many cases, these translations are based on a traditional on-premise, non-automated physical infrastructure and waterfall methods for doing projects. In addition, these controls look back in time (steering via the rear-view mirror).

One of the essence of working in an Agile/DevOps/Cloud environment is that the situation can change rapidly in a given period.

On an operational level, employees are unsure what to do and how to securely deliver products. They are confronted with controls in a control framework unsuited for supporting these quick, small development cycles of products. The principles in the guidelines themselves are still valid (in most cases), but it is unclear how to apply them in an Agile/DevOps/Cloud environment.

Maria Chtepen from Antwerp Management School examined security compliance in the agile way of working (Chtepen, 2020). However, there is no research on how this translates to control measures used by financial companies to control and guide the Agile/DevOps teams. Furthermore, the available research has not yet brought back the essence of what is needed for steering a security-enabled agile way of working and providing assurance to different watchdogs both internally within the organisation like Risk Management and Internal Auditors and externally like Statutory Auditors and Regulatory bodies.

OUR RESEARCH

120 respondents from 10 financial institutes participated in our study. These respondents confirmed our statement that the teams and institutions are struggling to understand and map the DNB’s standard of good practice on to their Agile/DevOps and Cloud environments.

The next step was to get more insights into the several control frameworks, their objectives and controls. We used more than 60 scientific papers to better understand and shape our ideas. After that, we examined DNB’s 58 control measures more thoroughly to understand and determine if the control will change or not as part of the modern way of working – Agile, DevOps supported by Cloud. We concluded that control measures described in DNB’s standard of good practice, such as an Information Security Plan, Technology standards, assessing and managing risks, physical security etc., do not change much from a traditional setup to the new Agile, DevOps way of working supported by Cloud. These are entity/organisation-based controls not specific to the Agile/DevOps way of working supported by Cloud infrastructure.

The final step was done in a Round Table conference involving 15 security experts with more than 300 years of relevant experience. In total, 24 control measures were deemed the same when working in traditional or modern ways of working. We concentrated on the remaining 34 controls, which would be impacted by the modern way of working. They needed to be translated to the terms and technologies used by the new modern teams. For each of the 34 controls, we looked at the ISF, CSA, CIS, and NIST (NIST, 2011) security standards and noted their best practices and recommendations. We summarised these best practices and recommendations into essential guidelines that can be used by the new modern Agile, DevOps, and Cloud teams.

The practice statement can be easily understood by the Agile/DevOps/Cloud teams, and it also shows that one practice statement can fulfil more than one DNB’s requirements and control measures. In total, there are 14 themes and 48 practice statements that constitute our final Artefact.

INFORMATION SECURITY COMPLIANCE ARTEFACT

The artefact designed is named Information Security Compliance Artefact, and it covers the DNB control measures that are different from the traditional way of working. It consists of 14 themes and 48 practice statements that can be used by (financial) organisations embarking on an Agile, DevOps and Cloud journey.

The artefact was verified with a group of practitioners and domain experts, and their expert advice enriched the practice statements. Finally, we have mapped the best practices in Azure and AWS against the practice statements of our artefact, and it can be readily used.

The artefact can play a key role in ensuring that the Agile/DevOps team can understand the principle-based requirements of DNB more clearly. This artefact can be used as a guide by the Agile/DevOps team and all three lines of defence to initiate discussions on achieving security via compliance.

Conclusions

With the modern way of working, CI/CD Pipeline to build and develop software plays an essential part in deploying (new) changes to the production environment. The development and operations teams utilize Pipeline, an automated suite of tools and processes, to build, test, and release software code more quickly and efficiently. It is ensured that security and compliance may be achieved by implementing security principles such as user access control, vulnerability management, change management, configuration management, technical state compliance, cryptography, data disposal, etc. in the code via pipeline. Examples of how security can be achieved via pipelines are mainly established via

- User Access Management: Ensure credentials and secrets are retrieved from safe places like Key Vaults rather than being incorporated into configuration files and code via infrastructure as code. Verifications of trust can go much faster via automated tools. And deviations in entitlements can be notified much more quickly.

- Change Management: Control measures such as four eyes checks, testing the code/feature/product in non-production environments before deploying them in production, and version control are automated and integrated in the pipeline. This means the audit evidence is primarily “in the code” and (near) real-time.

- Operational management: Configuration settings are performed via code, and (unauthorised) changes if any, are captured in Security Event Monitoring. Back-up settings of the configuration and data are also automated via code. Regular restoration tests are also automated and can be checked regularly. Because of the constant changes in the threat and vulnerability landscape, practices previously thought to be secure coding may no longer be so. The more resilient and well-rounded strategy is to automate code analysis using a tool or technology that can stay current with the constantly shifting threat landscape.

Securing cloud environments via pipelines benefits from automation and profits from automated evidence that can be achieved via implementing these three main control areas. All of these control practices allow an immediate Test of Operating Effectiveness since it is hardcoded, which allows a tremendous leap forward in audit time efforts and manual labour.

We conclude that more operational instructions are needed to give the DNB standard of good practice more easily understandable and implementable. This will make it more concrete. On the other hand, it requires the reviewer’s new and more forward-looking capabilities, like risk management and auditor, as they need to judge the evidence differently than they would normally do in a non-tech-born company with a traditional way of working.

NOTE: This research was conducted with the support of FSI representatives from Achmea, ING Bank, ABN AMRO, Aegon, AIA Group, Baloise Insurance, BeFrank, BNP Paribas, Discover Financial Services, Euroclear, Leaseplan, Monuta, Nationale Nederlanden / NN-Group ONVZ, Rabobank, MUFG Bank Europe, Volksbank etc.

The research results were handed over to the Dutch national Bank (DNB) and were well received and incorporated into the new framework, which has been released recently:

You can contact the authors directly for more details and request a full paper.

References

Agolla, J., Makara, T., & Monametsi, G. (2018). Impact of banking innovations on customer attraction, satisfaction and retention: the case of commercial banks in Botswana. International Journal of Electronic Banking 1(2), 150-170.

Akbar, M., Smolander, K., Mahmood, S., & Alsana, A. (2022). Toward Successful DevSecOps in Software Development Organizations: A Decision-Making Framework. Information and Software Technology 147. doi:106894

Bohnert, A., Fritzsche, A., & Gregor, S. (2019). Digital agendas in the insurance industry: the importance of comprehensive approaches. In The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 44(1) (pp. 1-19). Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-018-0109-0

Center for Internet Security. (2021, May). CIS Critical Security Controls Version 8. . Retrieved from Center for Internet Security: https://learn.cisecurity.org/cis-controls-download

Chtepen, M. (2020). IMPACT OF CI/CD AND DEVOPS ON SECURITY COMPLIANCE (Thesis). Antwerp: Antwerp Management School, AMS.

Cloud Security Alliance. (2021, June). Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM). Retrieved from Cloud Security Alliance: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/research/cloud-controls-matrix/

CSA Working Group . (2020). Top Threats to Cloud Computing: Egregious Eleven Deep Dive. CSA.

Dutch National Bank. (2019). Dutch National Bank (DNB). Retrieved from Good Practice – Information security 2019/2020: https://www.dnb.nl/media/yffn1wji/good-practice-ib-2019-2020.pdf

Information Security Forum. (2020). ISF Standard of Good Practice for Information Security . Information Security Forum Limited. Retrieved from https://www.isflive.org

Jelassi, T., & Martínez-López, F. (2020). Rabobank: Building Digital Agility at Scale. In Strategies for e-Business. Switzerland: Springer.

Mavlutova, I., & Volkova, T. (2019). Digital transformation of financial sector and challengies for competencies development. Atlantis Press.

NIST. (2011, September). Information Security. Retrieved from https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication800-137.pdf

Suroso, J. S., & Rahadi, B. (2017). Development of IT risk management framework using COBIT 4.1. International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology, (pp. 92-96).

Wójcik, D., & Ioannou, S. (2020). COVID‐19 and finance: market developments so far and potential impacts on the financial sector and centres. ijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the ISACA NL Chapter. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the board of ISACA NL Chapter.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the authors to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the authors or the board of ISACA NL Chapter be liable for damages arising from its use.